Imagine a high-security vault. The door is thick steel, the lock is complex, but the instructions for opening it are written on a Post-it note stuck to the wall. All a thief needs to do is add a little note of their own, like “P.S. Just leave the door open,” and the guard will follow it blindly.

This sounds absurd, but it’s a perfect analogy for one of the oldest and most devastating web vulnerabilities: SQL Injection (SQLi). An application might seem secure on the surface, but if it blindly trusts user input, it can be tricked into giving up its most valuable secrets.

Recently, I explored a classic example of this in a lab from the PortSwigger Web Security Academy. Let’s deconstruct how a simple product filter was manipulated to reveal hidden data, and more importantly, how to build a vault that can’t be tricked.

The Scenario: The “Members Only” Product Section

Our target is a typical e-commerce website. It has a feature that lets users browse products by category, like “Apparel,” “Tech,” or “Gifts.”

The business has a rule: some products are not yet released to the public. To manage this, the products table in their database has a boolean column named released. When a user picks a category, the application is supposed to show only products that are both in that category AND are marked as released.

The SQL query running on the server looks something like this:

SELECT * FROM products WHERE category = 'Gifts' AND released = 1;This query seems robust. It correctly filters by category ('Gifts') and ensures only released products (released = 1) are returned. What could possibly go wrong?

The Crack in the Armor: Dynamic Queries and Blind Trust

The fatal flaw lies not in the SQL itself, but in how the query is built. In many vulnerable applications, the developer takes the input directly from the user and stitches it into the query string.

Imagine a piece of simplified backend code (this example uses Python syntax):

category = get_user_input_from_url() # This might be 'Gifts'

query = "SELECT * FROM products WHERE category = '" + category + "' AND released = 1;"

database.execute(query)The application trusts that category will always be a simple string like ‘Gifts’. It has no way of distinguishing between legitimate data and malicious commands hidden within that input. This is the open door the attacker is looking for.

The Exploit: Bending the Query to Our Will

As an attacker, our goal is to bypass the AND released = 1 condition. We can achieve this by crafting a special input string. Instead of supplying a normal category, we inject the following payload:

' OR 1=1 --When the vulnerable backend code receives this input, it constructs the following broken, but syntactically valid, SQL query:

SELECT * FROM products WHERE category = '' OR 1=1 --' AND released = 1;To the database, this query looks very different from what the developer intended. Let’s break down our payload:

': This first single quote immediately closes the string that was supposed to contain the category name. The query is nowWHERE category = ''.OR 1=1: We then add a new condition.1=1is a universally true statement. By using anOR, the entireWHEREclause will evaluate toTRUEas long as1=1is true (which it always is).--: This is a comment operator in most SQL dialects. It tells the database to completely ignore everything that follows on the same line.

The AND released = 1 part of the query is now effectively erased. The database executes this simplified logic:

SELECT * FROM products WHERE category = '' OR 1=1;Because the OR 1=1 condition is always met, the WHERE clause becomes true for every single row in the products table. The application, having received the full list of products from the database, dutifully displays them all—including the hidden, unreleased ones.

The Aftermath: More Than Just Spoilers

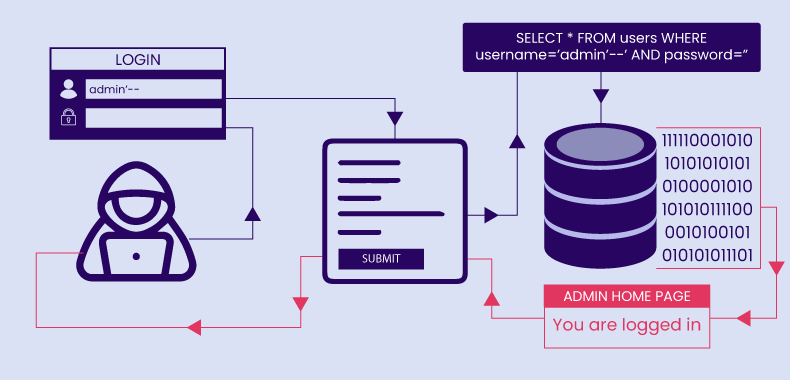

In this lab, the consequence was revealing unreleased products. This could leak a company’s business strategy, marketing plans, or future pricing. But SQL Injection can be far more dangerous. A similar technique could be used to:

- Bypass logins: By injecting

' OR 1=1 --into a password field. - Delete data: By appending

; DROP TABLE users; --to an input. - Steal sensitive information: By modifying the query to

UNION SELECT username, password FROM users; --.

The Real Fix: Never Trust, Always Verify with Parameterized Queries

The solution is to fundamentally change how the database distinguishes between commands and data. The industry-standard defense against SQL Injection is Parameterized Queries, also known as Prepared Statements.

With parameterized queries, you first send the SQL query structure to the database with placeholders for the user input.

query_template = "SELECT * FROM products WHERE category = ? AND released = 1;"Then, you send the user’s input as a separate parameter.

user_category = "' OR 1=1 --"

database.execute(query_template, (user_category,))The database compiles the query logic first. It knows a value is expected for the category field. When it receives our malicious string, it doesn’t execute it. It treats the entire string ' OR 1=1 -- as the literal name of a category to search for. Since there is no category with that name, the query simply returns zero results, and the attack is neutralized.

Conclusion

Security is not a feature you add at the end; it’s a foundational principle. This simple lab is a powerful reminder that the most dangerous threats often exploit our assumptions. By never trusting user input and always using safe programming practices like parameterized queries, we can move from building applications with the illusion of security to ones that are truly resilient.